Survival of Los Banos Internment Camp: The Story of Patty Kelly Stevens

On February 23, 1945, the U.S. Army Airborne and Filipino guerrilla task force combined their efforts to liberate 2,147 Allied civilian and military internees from Los Banos Internment Camp, a Japanese prison camp. One of these prisoners was Patty Kelly Stevens and her family. During World War II, Patty’s mother, Selma Croft, hid the family’s U.S. flag under threat of death as they were held prisoners for three years in the Philippines. The flag, which briefly flew over Los Banos Camp, became a symbol of hope for the prisoners there in the weeks before they were rescued.

(Image source: WikiCommons)

The History of the Flag

The flag’s story begins long before the war.

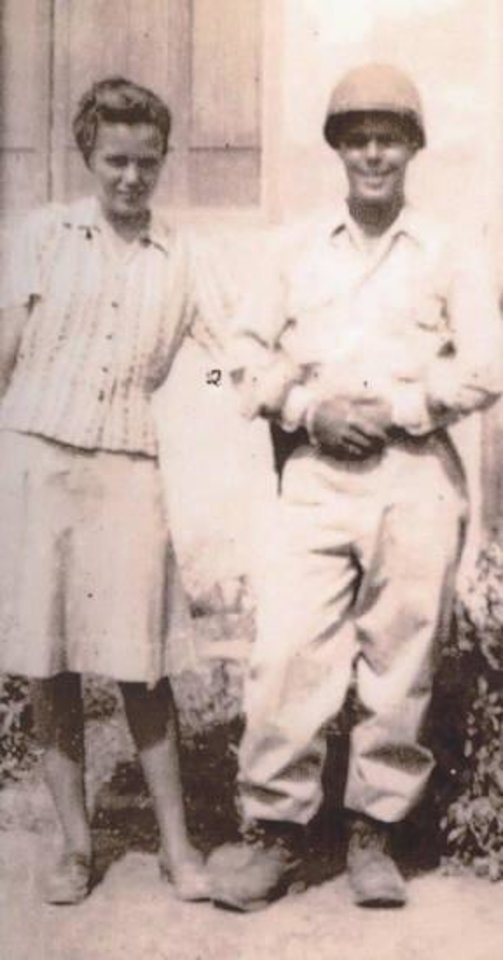

Alfred Croft, Patty’s father, was a self-taught pilot who served in World War I and had come to the Philippines in 1918 to help train Filipino flyers. There, he met Selma, who was a private duty nurse. The two married and lived in China and then Hawaii, where Patty was born, before returning to Manila.

One night during a festival in the early 1920s, a fire broke out. There was an American flag flying over the carnival, which Alfred Croft rescued from the flames. General Leonard Wood, then Governor General of the Philippines, was so appreciative that he awarded the flag to Croft.

For two decades, the flag stayed in the Croft family. They lived an easy life in the Philippines, Patty said. That was until WWII began and the U.S. government started sending American families back to the U.S. Patty’s family could not get their passports, and unfortunately couldn’t get out in time before things started getting bad.

was a manufacture of flags and bugles in the 1800’s & early 1900’s.

Imprisonment At the Camp

Manila was declared an open city, so on January 6, 1942, Japanese Soldiers came to the door and told the Croft family to pack enough food and clothing for three days. Patty was only months away from graduating high school and moving to California. Instead, Japanese Soldiers ordered her to put her life on hold. The three days turned into three years and two months. Unbeknownst to Stevens, her mother packed the family’s American flag with her things. For three years, Selma Croft would keep the flag hidden.

At first, they were placed at the University of Santo Tomas. Patty later stated that it was not equipped as a prison camp to hold 6,000 people. There were no showers, mosquito nets, and they slept on the floor until the Filipino Red Cross brought the prisoners beds. As Santo Tomas grew more crowded, the Japanese sent prisoners to build another camp on the island of Luzon, a camp that would become known as the Los Banos Internment Camp. Patty’s brother, then only 14 years old, was sent to help build the camp. He would never be the same, she later said.

Patty’s family moved to the camp at Los Banos in December 1944. It was supposed to be better, but it wasn’t. Prisoners were starved, and Patty could barely walk by the end of her imprisonment. On January 9, 1945, prisoners were awakened by screams at 3:45 in the morning. They learned that the Japanese Soldiers had fled the camp because they feared that American troops were coming.

Someone asked for a flag, and Patty’s mother produced her treasured flag that she had been hiding for nearly three years. The same flag General Wood had awarded to her husband 20 years before. The Americans raised the flag over Los Banos and sang “The Star Spangled Banner.” For a week, the prisoners lived like kings, breaking into the food storage and eating more than they had in years. But even with no guards, most of the 2,000 prisoners were unable to leave. There was simply nowhere else to go.

After 7 days, the Japanese did return and had somehow heard about the flag. They searched the barracks three different times, but luckily, the Americans who had raised it on the flag pole, had not returned it yet to Patty’s mother after they lowered it. Patty said that her family would have been executed on the spot had the Japanese found the flag. Once they were in the clear, the flag was returned to Patty’s mother. She continued to hide it until they were rescued.

The Raid At Los Banos

On February 23, 1945, the prisoners were lined up, scheduled to be executed. However, the Japanese Soldiers did not know that three men had escaped the camp to warn General Douglas MacArthur about the pending mass execution. Before the prisoners could be killed, Paratroopers from the 11th Airborne Division and the 672nd Amphibian Tractor Battalion and a Filipino guerrilla task force executed one of the most successful rescue operations in military history, liberating 2,147 Allied civilians and military prisoners.

As Filipino guerillas attacked from the ground, U.S. troops with the 11th Airborne Division came from the sky.

“It was the happiest day of my life,” Stevens said. “To see those paratroopers come.

With bullets flying, the family hid under their beds. But the Allied forces quickly overran the Japanese guards. Patty said her freedom came with the sound of footsteps as one of the soldiers entered the barracks.

“Are you a Marine?,” she asked.

“Hell no. I’m not a Marine. I’m a paratrooper,” the man responded.

The Continued Legacy of the Flag

In 2018, Patty Kelly Stevens made the decision to donate the cherished flag to the U.S. Army Airborne and Special Operations Museum. The donation was made on the 73rd anniversary of the Los Banos Raid. “I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for the airborne,” Patty simply stated.

Melissa Gerrits of the Fayetteville Observer.

The flag still resides in the ASOM’s collection, where it helps educate the public on the legacy of Airborne and Special Operations Soldiers.

Did you enjoy this content? If so, please consider giving a gift to the ASOM to help us continue our mission.